When two or more people own the same property, one of the owners CAN force a sale of the jointly owned property via a partition action or lawsuit. If you are dealing with joint ownership property, this guide explains the cost of a partition action, how to win a partition action, whether a partition action can be stopped, and more.

As a real estate attorney who deals with forced sales regularly, I prepared this guide based on direct research and experience.

Use the links below to view legal forms related to partition and forced sale, or contact an attorney.

— Ryan Jones, Esq.

Joint Property Ownership When One Party Wants to Sell

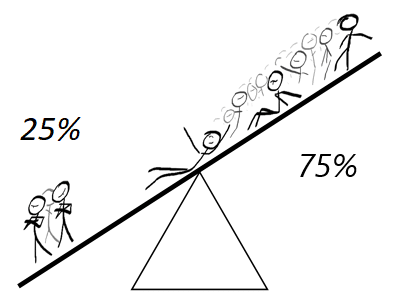

What are the legal rules for joint property ownership when one party wants to sell? The minority owner CAN force a sale against the will of the majority owners. The law allows any co-owner to fracture the joint ownership via a partition action.

Yes! In most cases, ANY co-owner (even a minority owner) can force a sale of the property regardless of whether the other owners want to sell or not.

How can that be? Shouldn’t the majority opinion control? Normally, yes. But when it comes to co-ownership, the law cannot really force co-owners to remain as co-owners. Imagine the problems that would arise if a court forced divorced spouses, warring siblings, or estranged business partners to remain in a co-ownership relationship.

For this reason, the law provides an unquestionable “out” for any co-owner who no longer wishes to remain on title.

Forced Sale Meaning: What is a Forced Sale of Property?

A forced sale is a legal process (often called a partition lawsuit) by which the co-owner of a property can accomplished a court-ordered sale of the jointly owned property. The sale occurs under court supervision, ending in division of the property or sale proceeds.

But wait! Is a lawsuit the only way to force a sale?

You should only file a lawsuit as the last resort. I have seen far too many legal battles leave everyone worse off than when the lawsuit began. So before going down the dreary road to the courtroom, let’s first consider whether you might be able to force a sale outside of court.

Often, a sale can be “forced” merely through persuasion or the threat of a partition lawsuit. Do not skip over the negotiation phase! Before a lawsuit has been filed, you have a chance to convince the other co-owners that selling the property (or keeping the property) is the best course of action for everyone.

- Put yourself in the other co-owner’s shoes. Figure out what they want and why they want it.

- Overlook your emotional frustrations with this person and focus on their motivations.

- Lay out exactly why and how the other co-owners will be harmed if you end up in court.

- Explain how a voluntary sale (or a buyout) would prevent the wasteful and painful process of litigation.

- Propose a specific course of action (buyout, voluntary sale, or keep the property).

When I send letters like this on behalf of clients (with much more detail), the co-owners often reach an agreement on how to sell or consolidate ownership, thereby preventing a costly lawsuit. If you would like to send a letter to your co-owners, you can do using a user-friendly automated document:

In short, a lawsuit is not the only way to force a sale.

You can force a sale, prevent a sale, or accomplish a buyout through honest persuasion. Stay solution oriented, and use the mere threat of a partition lawsuit to motivate everyone toward your solution.

But what if persuasion fails? Enter the partition lawsuit.

Partition Lawsuit Definition: What is a Partition Action?

A partition lawsuit (or a partition action) is a legal process by which a court either divides up a property among the co-owners or sells the property and divides the money among the co-owners. A partition action “splits the baby” when the owners cannot agree. Partition simply means “division”.

Obviously, no one literally wants to split the baby. And no one literally wants to cut a house in half. But strangely enough, the partition process begins with the following question:

Can we literally divide up the property between its owners?

If possible, Courts prefer to divide the property in equal pieces and give each joint owner a piece. However, this sort of literal division only occurs with land, acreage, or rural property that can be doled out in equal pieces. Courts cannot literally split a residential property, for the obvious reason depicted above.

If the Court cannot divide the property itself, then it must be sold at a sheriff’s auction with the purchase price divided among the owners. For example, if each person owns 50%, each person receives 50% of the money when the property sells. Along the way, any of the co-owners can exercise the right to buy out the other co-owners based on the appraised value.

BUT, see the discussion below regarding adjustment of profit splits based on “fairness” factors.

Since a partition lawsuit requires court approval, the process takes several months. The Plaintiff must name each co-owner as a party to the lawsuit and follow detailed legal procedures. The specific procedures depend on state law.

To simplify the process, an appraiser values the property and then the sheriff sells it at a public auction. Everything occurs under Court supervision. Statutory safeguards prevent the property from selling for scraps, but it will likely sell at a substantial discount. To ensure that the property brings a decent price at the auction, it is very important to market the property prior to the auction. Work with a real estate attorney and a real estate agent who understand the partition process. Otherwise, you may end up with an undervalued property, or you may have no bidders at the auction.

How to Win a Partition Action

If you want to sell the property, you win by pressuring a voluntary sale or by obtaining a court order for sale. If you want to STOP a sale, you win through a buyout or by convincing the other owners to halt the partition action.

What does it really mean to “win” a partition action? In my opinion, winning means preventing or ending the lawsuit altogether. Dragging the property through a full partition process can drain the equity from the property and drain the energy from its owners.

So in my book, winning a partition action means reaching a voluntary resolution that works in everyone’s favor. That does not mean everyone will get everything they want. It means everyone will compromise.

And how do you convince your co-owners to compromise? You prove to them that a partition lawsuit is a lose-lose scenario. Show them through legal citations and financial calculations that fighting a court battle will leave everyone worse off.

Make them choose the lesser of two evils. A buyout or voluntary sale might be less than ideal. But it sure beats paying thousands in attorney fees while the property sits tied up in a court proceeding for months or even years.

For more detailed guidance on the steps to “win” or navigate a partition action, see the step-by-step guide at the end of this article.

If a resolution fails, the party seeking a sale of the property will probably “win” the partition action. The law generally allows any co-owner to force a sale, and it is difficult or impossible to prevent that from happening. So, if your goal is to prevent the sale altogether, a buyout or a voluntary agreement may be your only option.

Can a Partition Action be Stopped?

The short answer is no, a partition action cannot be stopped. Each co-owner has an “absolute right” to partition. This is difficult or impossible to overcome. However, it may be possible to voluntarily halt the partition through negotiation or through a buyout of the co-owner’s interest. Also, there are certain narrow exceptions when the co-owners are spouses or ex-spouses. In certain states, family law and divorce impacts the ability of spouses to partition marital property. But otherwise, any co-owner can seek partition at almost any time.

"A co-owner's right to partition is absolute."

As explained above, partition law allows the minority to rule by tyranny. Okay, that’s a little dramatic. But it’s true that the party seeking a sale generally has the upper hand.

Keep in mind, however, that forcing the sale does not equate to keeping the money. As explained below, the court can rearrange the money splits based on “fairness” factors. Just because you get an order for sale does not mean you will walk away with lots of money.

Do it Yourself or Hire an Attorney?

What is the better way to solve your joint ownership issue? Sometimes, legal counsel is necessary and should not be avoided. But there are also advantages to handling the joint ownership issue yourself (with appropriate legal forms, tools, and education).

Both options can be effective depending on your situation, personality, and preferences. We don’t try to scare clients into hiring an attorney. We aren’t biased either way. It’s 100% your choice.

The Cost of a Partition Action

How much are attorney fees?

Attorney fees for even the most simple of partition actions could exceed $5,000. Even if the partition lawsuit is uncontested, there are many steps and lots of paperwork, which requires a significant amount of attorney time. And if the matter is contested or complicated, costs can exceed $15,000 or even $20,000. If you do not request a pricing estimate, you may not even realize how much the costs are adding up, because many attorneys charge on an hourly basis. Often, attorney fees can be paid from the proceeds when the property sells. However, this assumes that the property will indeed sell at some point. If for any reason the sale does not occur, you may still be liable for the attorney fees incurred.

How much are DIY legal forms?

By handling the partition action yourself, with appropriate guidance and legal tools, you can save significant attorney fees. Our firm offers legal forms specifically designed to solve joint ownership issues. These forms can cost anywhere from $95 to $500 depending on whether the case goes to court or not. In other words, legal forms are less than one-tenth the cost of an attorney.

Now, does that mean DIY legal forms are always the best option? Not necessarily. If there is a lot of money at stake, it might be worth your money to pay for a professional. This is a choice only you can make, and we do not push you one way or the other.

Timeframe or Length of a Partition Action

A forced sale or partition action can take 6-12 months on average. In some states, the partition could technically be completed faster, but due to inevitable complications and roadblocks, you should not expect to be done any sooner than 6 months.

When you hire an attorney, you give up control over the timeline of your partition. You are now on the attorney’s schedule, not your own. You cannot control how busy the attorney might be, or whether they have personal emergencies, which can extend the timeframe for completion. If you handle the action yourself, you stay in the driver’s seat and you can push the case along as quickly as possible. But at the same time, if you handle the partition yourself, you may encounter delays due to your inexperience as compared to a legal professional. It’s a double edged sword.

How Doing it Yourself can Lead to Voluntary Solutions

Even if a partition lawsuit is filed, you should always be looking for a voluntary solution. When you handle the partition action yourself, you are very familiar with the details, rules, and financial factors at play. This allows you to negotiate with the other co-owners and make informed decisions about settlement. In other words, you cut out the middle man (the attorney). This puts you closer to the action and allows you to communicate in real time with the court and the other co-owners about a voluntary sale, buyout, or other solution.

That said, some partition actions can become quite complex, so representing yourself is not advisable in every circumstance. Even if you don’t represent yourself in court, you should always attempt to negotiate directly with your co-owners before hiring a lawyer. If you can reach a voluntary solution, you may be able to avoid unnecessary conflict and legal fees.

How to Force the Sale of Jointly Owned Property (step-by-step)

In short, to force the sale of jointly owned property, you must first confirm title, then attempt a voluntary sale or buyout, file and serve a partition lawsuit, get an appraisal, sell the property, and finally divide the sale proceeds fairly.

The exact order and details of these steps may vary from state to state, or from judge to judge. However, the same general process will apply nearly universally.

Step 1: Confirm title to the jointly owned property.

Make sure you understand current ownership. Clarify who owns what percentage of the property. If necessary, obtain a title report from a title company. You don’t need a full title opinion; you just need a title report. Many title companies provide a title reports showing current ownership for a flat fee around $100.00. If you end up filing a partition action, you will need copies of the deeds or instruments vesting title in the joint owners.

Step 2: Identify the benefits and burdens of ownership.

After confirming ownership, try to identify the “benefits and burdens” of ownership.

The “burdens” of ownership include taxes, mortgage payments, repairs, and improvements. Basically, identify who paid money or suffered financial detriment for the property. Whoever bore the financial burdens of ownership might receive a greater share of proceeds from the sale. You want to know this in advance.

Likewise, determine the “benefits” of ownership. Has one person been living at the property, leasing it, or enjoying it more than the other owners? This person might suffer a reduction in sale profits due to the disproportionate benefits received in the past.

In short, get a basic idea of the economic factors at play. If someone bore a disproportionate share of the property burdens, they typically receive a greater share of the profits. If someone enjoyed a disproportionate share of the property benefits, they typically receive a lesser share of the profits.

Step 3: Attempt a voluntary sale, buyout, or alternate solution.

Even if you think litigation is inevitable, always try hard to accomplish a voluntary solution. A voluntary sale on the open market brings more money than a forced sale at auction. A voluntary buyout also prevents the loss in value resulting from litigation. So, make every effort to resolve differences with the other co-owners.

Regardless of whether you reach an agreement, you will look better in court if you can provide evidence that you tried hard to resolve the situation before filing a lawsuit.

If the other owners will not agree, you can put some pressure on them. Send them a letter, preferably with an attorney’s assistance, which spells out the law on forced sales and partitions. Using numbers and legal citations, prove to them that a partition action would hurt all of the co-owners financially and emotionally. Faced with this reality, the other co-owners might begin to think more seriously about a voluntary solution.

Step 3: File and serve a partition lawsuit.

Failing a voluntary solution, prepare and file your partition action. This legal filing must follow state partition statutes. A partition action does require some legal work, so many co-owners prefer to hire an attorney at this stage. However, you are NOT required to hire an attorney, and you have the right to file or defend a forced sale or partition yourself. See the section above explaining the disadvantages of hiring an attorney.

In short, your partition lawsuit should name as defendants all co-owners and anyone who claims an interest in the property, such as mortgage or lien holders. The lawsuit must be served on all parties in accordance with state law.

Step 4: Determine whether property division is possible.

If dealing with rural property, land, or acreage, the Court may prefer to literally divide up the property itself and give each co-owner a piece. This process, called “division in-kind” can only happen for land and acreage. In the partition lawsuit, the judge typically determines whether to divide the property itself, or forcibly sell the property and divide the proceeds.

Step 5: Get an appraisal.

The partition process requires an appraisal. Real estate professionals typically must be appointed and approved by the judge. The professionals or appraisers value the property and file a report in the court record. The appraised value is generally used if any of the co-owners exercise the right to buy out the other owners. And in many states, the property cannot sell at auction for less than 2/3rds of the appraised value.

Step 6: Sell the property.

If the Court approves the partition action, you must coordinate a forced auction through the sheriff’s office (or the local equivalent). The sheriff accepts bids from the public and deeds the property to the new owner. Ensure that you adequately market the property prior to the auction. The sheriff will not do a good job of marketing the property. Preferably, use a real estate agent who understands the forced sale process. If only a few bidders show up at the auction, you may suffer a decrease in sale price.

Step 7: Divide the proceeds.

As a general rule, the sale proceeds are split according to ownership interests. If you own 10% of the property, you get 10% of the proceeds after deduction of fees and costs. Attorneys typically get paid from the proceeds as a cost of the action. However, the profit splits may change if one of the co-owners calls for an “accounting.” To put it simply, an accounting occurs when the Court evaluates the “burdens and benefits” of ownership, as discussed above. The Court “takes into account” each party’s level of investment and benefit, and if necessary, the Court adjusts profit splits to achieve a fair outcome. This adjustment process may not happen unless someone calls for an accounting.

How does the money get split?

Normally, the Court divides up the money in proportion to ownership interests. If you own 75% of record title, then you get 75% of sale proceeds. Attorney fees, realtor costs, and Court costs may reduced your share of profits.

But what if that’s not fair?

What if one owner pays the mortgage, taxes, and all expenses?

What if one owner invested lots of money in the property?

Certain factors can change the amount of money each owner receives from the sale, regardless of record title ownership. The profit splits can change based on “fairness” factors. Even if each person owns half of record title, one person might receive more than half of the money due to unequal sharing of property burdens or property benefits.

The process for adjusting money splits is often called an “accounting.” Each party can call for an accounting during the partition lawsuit. As part of the accounting, the Court “takes into account” each party’s level of investment in the property. How much did each party benefit from the property? How much did they spend? Crunch the numbers and determine the most equitable division of profits.

Before calling for an accounting, keep in mind that an accounting costs money. Fighting over numbers costs lots of attorney fees. The attorneys probably get paid from the sale proceeds. So, if you spend several thousand in attorney fees to get an extra 10% of the profits, your extra profit might get eaten up by your extra attorney fees. Don’t call for an accounting unless the accounting significantly increases your share of profits.

Can Siblings Force the Sale of Inherited Property?

Yes, siblings (or other co-owners) can force the sale of inherited property via a partition action or lawsuit. If you are dealing with this situation, you should understand the legal rules and pitfalls surrounding forced sales and partition actions. This article provides a thorough overview.

Are there any special rules for forced sales involving siblings or inherited property? Generally, the same rules apply to jointly owned inheritance property as to any jointly owned property. So, the bulk of this article should apply to a sibling situation. That said, family dynamics and family history can play crucial role with respect to negotiation and division of proceeds.

During the negotiation phase before a lawsuit has been filed, it is critical to account for the emotions of all co-owners. Do not expect rational emotions or logical decisions in the wake of a loved one’s death. When approaching co-owners with a solution, start with their emotions, motivations, and desires, and work from there.

If you have to compromise beyond what is "fair" to achieve a solution, then by all means, do it. When it comes to family matters, an imperfect but voluntary solution is almost always better than a lawsuit.

But, if a lawsuit becomes unavoidable, remember that the family history can play a role in how the court doles out money from the forced sale of a jointly owned property. Within families, money, services, and property often change hands without adequate documentation. When it comes time to divide the money, the unwritten details may surface and impact the court’s decision about what is fair.

Can Divorced Spouses Force a Sale?

Yes, a divorce spouse can generally force a sale via partition if necessary. When the romantic relationship dies, the co-ownership relationship likely dies along with it. One party moves out, and the remaining party assumes control of the property and full responsibility for the mortgage. But what if they stop paying the mortgage? Maybe the occupant agreed to pay the mortgage, but the party who moved out is still equally responsible for the loan. So, if the occupant stops paying, the absent party will take a credit hit. If the occupant refuses to sell voluntarily, the only option may be a forced sale.

Keep in mind that married couples may be prevented from forcing a sale due to state laws on marital property, community property, and family law.

How will you resolve your joint ownership issue?

That said, some partition actions can become quite complex, so representing yourself is not advisable in every circumstance. Even if you don’t represent yourself in court, you should always attempt to negotiate directly with your co-owners before hiring a lawyer. If you can reach a voluntary solution, you may be able to avoid unnecessary conflict and legal fees.